Editor’s Note: Adam H. Sobel, a professor at Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory and Fu Foundation School of Engineering and Applied Science, is an atmospheric scientist who studies extreme events and the risks they pose to human society. Sobel is the host of the podcast “Deep Convection” and the author of “Storm Surge,” a book about Superstorm Sandy. Follow him on Twitter: @profadamsobel. The opinions expressed in this commentary are his own. View more opinion on CNN.

There have been so many floods, in so many parts of the world, in such a short period of time.

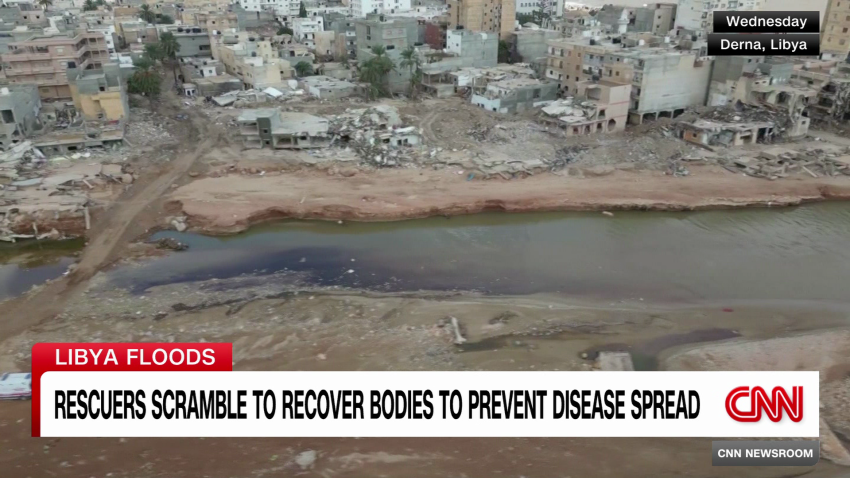

In the past few weeks alone, there have been major flood events in Massachusetts, Hong Kong, Greece and Spain. The greatest catastrophe was in Libya, where heavy rains associated with storm Daniel in the Mediterranean caused dam failures and led to a death toll that is at least several thousand, and could exceed 10,000 once the missing are accounted for, according to the Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs.

What is causing so many extreme floods at once? Is this climate change, or just a particularly severe bunch of weather flukes happening in close succession due to the climate’s own natural variability?

As is typically the case, it’s probably some of both. And while we can say some things with confidence about the role of global warming in these kinds of events, there’s plenty more we can’t say. But those uncertainties don’t reduce the risks, and shouldn’t make us less committed either to the clean energy transition or climate adaptation. In fact, they should make us more committed.

This is what we know: Overall, extreme rain events are becoming both more frequent and more extreme across much of the planet, and this is an expected and predicted consequence of global warming.

There’s more water vapor in warmer atmospheres; we understand well why this should be the case, and we observe that it is the case. The heaviest rain events are the ones that are the most efficient at condensing that water vapor out into rain, and if there’s more water vapor to be condensed, the rains get heavier. This is a simple physical argument, but our very sophisticated computer models for predicting weather and climate also support it.

The details of individual storms are more complex, though.

A particularly rare event like Daniel in Libya has to involve other factors besides water vapor. In particular, the flooding in Greece, Spain and Libya all occurred in the presence of a weather pattern called “blocking,” where the upper atmospheric flow is distorted by a persistent high pressure system. This can cause major storms to occur in places where they’d otherwise be rare.

Blocking happens naturally. But climate change acts by loading the dice on many types of weather events. So, is it possible that blocking, and the unusual storms that can accompany it, could be happening more often with warming? It is. But here, the science is on less solid ground.

It has indeed been argued that warming causes blocking to become more prevalent. The evidence for this is mixed at best though, and many scientists with expertise in this problem are not convinced. I am one of the unconvinced, but I am keeping an open mind. While we know a lot about how warming affects extreme weather, there’s a lot we don’t know, too, and the effects of global warming on blocking is one area of ongoing research and debate.

El Niño may also have been a factor in these recent floods. El Niños are short-term climate phenomena in which the eastern equatorial Pacific Ocean surface becomes unusually warm, which temporarily alters the atmospheric circulation all over the planet. A recent study linked “East Pacific El Niños” with increased blocking over Europe in particular.

Like blocking, El Niños occur naturally. Our climate models predict, however, that greenhouse warming will cause the Pacific to trend more towards an El Niño-like state as it warms. If the models were right, this would imply another way in which human influence could share some of the blame for the current El Niño, thus also the blocking event, and thus the floods.

But the last half century or more of observations suggest that the models may be wrong: The Pacific has been trending more towards the opposite, a La Niña-like state, in which the eastern equatorial Pacific becomes unusually cool instead of warm, and the atmospheric circulation shifts in near-opposite ways to what happens in an El Niño. But there are multiple interpretations of the disagreement, and this, too, is a very live scientific debate.

Since El Niños and La Niñas cause opposite effects in many places, this uncertainty about which will become more prevalent in the future throws a wrench into our ability to predict many specific aspects of climate change, such as its effect on hurricanes.

Because of all these complexities, it can be difficult or even impossible to reach a conclusion about the role of climate change in some extreme weather events, including Daniel. That shouldn’t be comforting; climate change could be playing a larger role than we expect in many of these events. From a global risk management perspective, these kinds of catastrophes should make us more motivated to stop burning fossil fuels.

At the same time, we have to do our best to adapt to the climate that’s here now. Among other things, this means maintaining basic infrastructure. It appears that the real catastrophe in Libya was due to the failure of the dams, an outcome that was probably preventable. Here in the US, we have a lot of old dams that are not in good shape. Even without climate change, it would behoove us to catch up on their maintenance, or, where these dams are no longer truly needed, remove them. What we know about climate change and extreme weather should strengthen that motivation; what we don’t know should strengthen it even more.