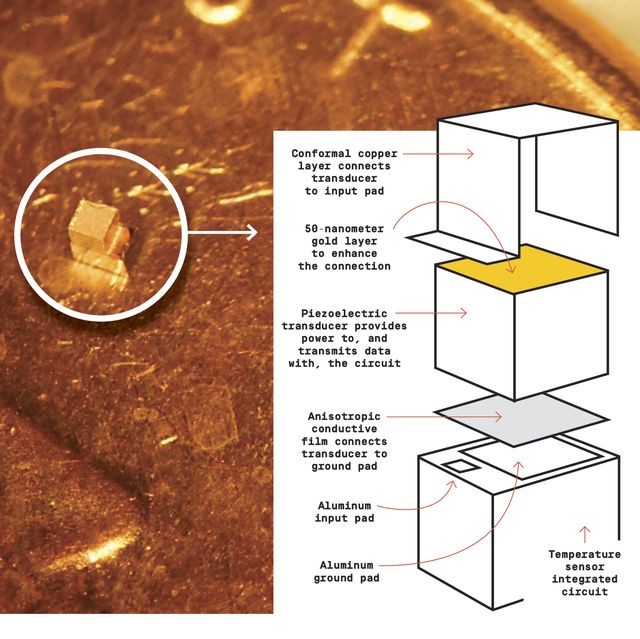

Scientists at Columbia University have created the world’s smallest microchip, which can be implanted into the body and may eventually be able to detect medical conditions such as strokes. The chips, called motes, are the size of dust mites, measuring less than 0.1 cubic millimeter, and can only be seen under a microscope.

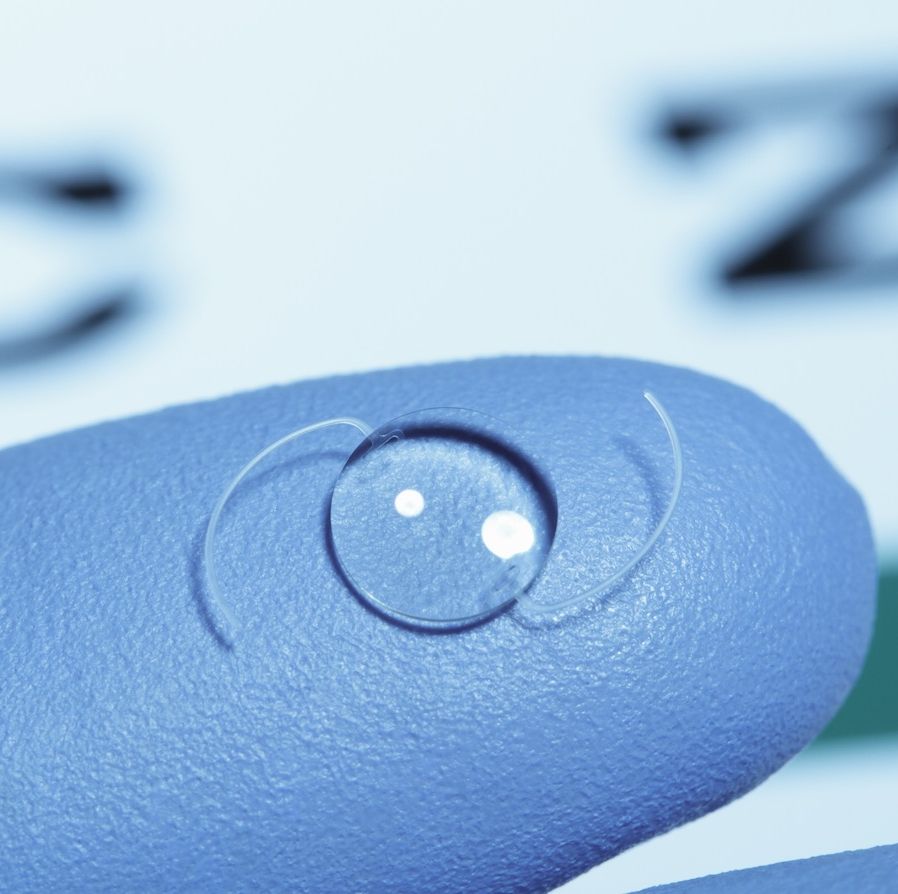

Motes operate as a single-chip system, complete with their own electronic circuit. They’re implanted via hypodermic needle, and the data they collect is read using an ultrasound machine. And though the chips have only been tested in lab rats, the Columbia team hopes that one day they can assist in monitoring everything from glucose levels to oxygen saturation.

“These devices can be designed to sense things and communicate this information back to the ultrasound image, which also provides biogeographical data on where this particular information was sensed,” says lead researcher Ken Shepard, Ph.D., professor of electrical engineering and biomedical engineering at Columbia.

The motes’ data transmission and power are both wireless. The interface that connects the human to the technology is integrated on the chip itself. And the device is small enough to be unobtrusive and amenable to the human body.

To power the chips, the scientists apply ultrasonic waves. (The motes run only when activated by an ultrasound machine.) Ultrasonic wavelengths are much smaller than the radio wavelengths used for most wireless communication, allowing the chip’s extremely small size.

The chips are built with the same complementary metal-oxide-semiconductor (CMOS) process used in chips for computers, cars, and smartphones. CMOS chips are made with a pair of semiconductors attached to a secondary voltage source so that they work at opposite times; when one transistor is switched on, the other is switched off.

💉 A Brief History of Revolutionary Medical Implants

To have the chips communicate with ultrasound technology, researchers added a microscale piezoelectric transducer. It converts mechanical sound waves from the ultrasound machine into electrical signals and vice versa. It’s covered with a small layer of gold on both sides to enhance connectivity. The motes also feature a layer of special conductive film and a thin sheet of copper.

“These are added after we get the chips back from the commercial foundry,” Shepard says. “In addition, we have to etch and thin the chips to these very small form factors and coat them with a kind of plastic for biocompatibility.”

So far, the Columbia University team has successfully demonstrated the use of motes to monitor body temperature in rats—injecting the chips into the rodents’ brains and hind legs to evaluate the chips’ temperature-sensing performance—but human use will require considerable testing and FDA regulation.

Shepard and his team believe the motes will eventually prove useful in monitoring data other than temperature, from respiratory conditions to blood pressure. He says this could streamline the way we diagnose and treat diseases. In the future, implantable tech might be how your vitals are taken before a surgery or how tumors are located in a specific organ, or they might even be used in therapeutic settings to help treat chronic illnesses.