Graphene Study Confirms 40-Year-Old Physics Prediction

A team of researchers from Columbia University, City University of New York, the University of Central Florida (UCF), and Tohoku University and the National Institute for Materials Science in Japan, have directly observed a rare quantum effect that produces a repeating butterfly-shaped energy spectrum, confirming the longstanding prediction of this quantum fractal energy structure called Hofstadter’s butterfly. The study, which focused on moiré-patterned graphene, is published in the May 15, 2013, Advance Online Publication (AOP) of Nature.

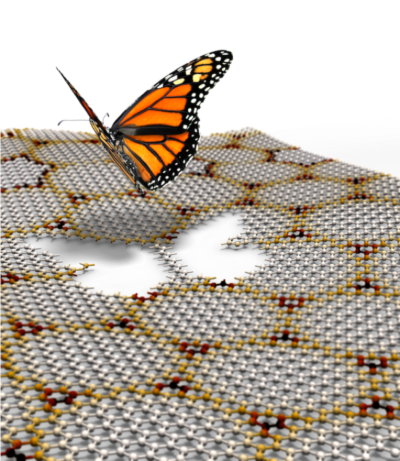

Illustration of butterfly departing from graphene moiré pattern formed on the top of atomically thin boron nitride substrate. Electron energy in such graphene moiré structure exhibits butterfly like self-recursive fractal quantum spectrum.

First predicted by American physicist Douglas Hofstadter in 1976, the Hofstadter butterfly emerges when electrons are confined to a two-dimensional sheet, and subjected to both a periodic potential energy (akin to a marble rolling on a sheet the shape of an egg carton) and a strong magnetic field. The Hofstadter butterfly is a fractal pattern—it contains shapes that repeat on smaller and smaller size scales. Fractals are common in classical systems such as fluid mechanics, but rare in the quantum mechanical world. In fact, the Hofstadter butterfly is one of the first quantum fractals theoretically discovered in physics but, until now, there has been no direct experimental proof of this spectrum.

Previous efforts to study the Hofstadter butterfly, which has become a standard “textbook” theoretical result, attempted to use artificially created structures to achieve the required periodic potential energy. These studies produced strong evidence for the Hofstadter spectrum but were significantly hampered by the difficulty in creating structures that were both small and perfect enough to allow detailed study.

In order to create a periodic potential with a near-ideal length scale and also with a low degree of disorder, the team used an effect called a moiré pattern that arises naturally when atomically thin graphene is placed on an atomically flat boron nitride (BN) substrate, which has the same honeycomb atomic lattice structure as graphene but with a slightly longer atomic bond length. This work builds on years of experience with both graphene and BN at Columbia. The techniques for fabricating these structures were developed by the Columbia team in 2010 to create higher-performing transistors, and have also proven to be invaluable in opening up new areas of basic physics such as this study.

To map the graphene energy spectrum, the team then measured the electronic conductivity of the samples at very low temperatures in extremely strong magnetic fields up to 35 Tesla (consuming 35 megawatts of power) at the National High Magnetic Field Laboratory. The measurements show the predicted self-similar patterns, providing the best evidence to date for the Hofstadter butterfly, and providing the first direct evidence for its fractal nature.

“Now we see that our study of moiré-patterned graphene provides a new model system to explore the role of fractal structure in quantum systems,” says Cory Dean, the first author of the paper who is now an assistant professor at The City College of New York. “This is a huge leap forward—our observation that interplays between competing length scales result in emergent complexity provides the framework for a new direction in materials design. And such understanding will help us develop novel electronic devices employing quantum engineered nanostructures.”

“The opportunity to confirm a 40-year-old prediction in physics that lies at the core of most of our understanding of low-dimensional material systems is rare, and tremendously exciting,” adds Dean. “Our confirmation of this fractal structure opens the door for new studies of the interplay between complexity at the atomic level in physical systems and the emergence of new phenomenon arising from complexity.”

The work from Columbia University resulted from collaborations across several disciplines including experimental groups in the departments of physics (Philip Kim), mechanical engineering (James Hone), and electrical engineering (Kenneth Shepard) in the new Northwest Corner building, using the facilities in the CEPSR (Columbia’s Schapiro Center for Engineering and Physical Science Research) microfabrication center. Similar results are concurrently being reported from groups led by Konstantin Novoselov and Andre Geim at the University of Manchester, and Pablo Jarillo-Herrero and Raymond Ashoori at MIT.